Your basket is currently empty!

The tale of Macigna and the passage to the underworld “The Hellmouth”

“An old folktale

of a passage to the underworld through a dangerous cave

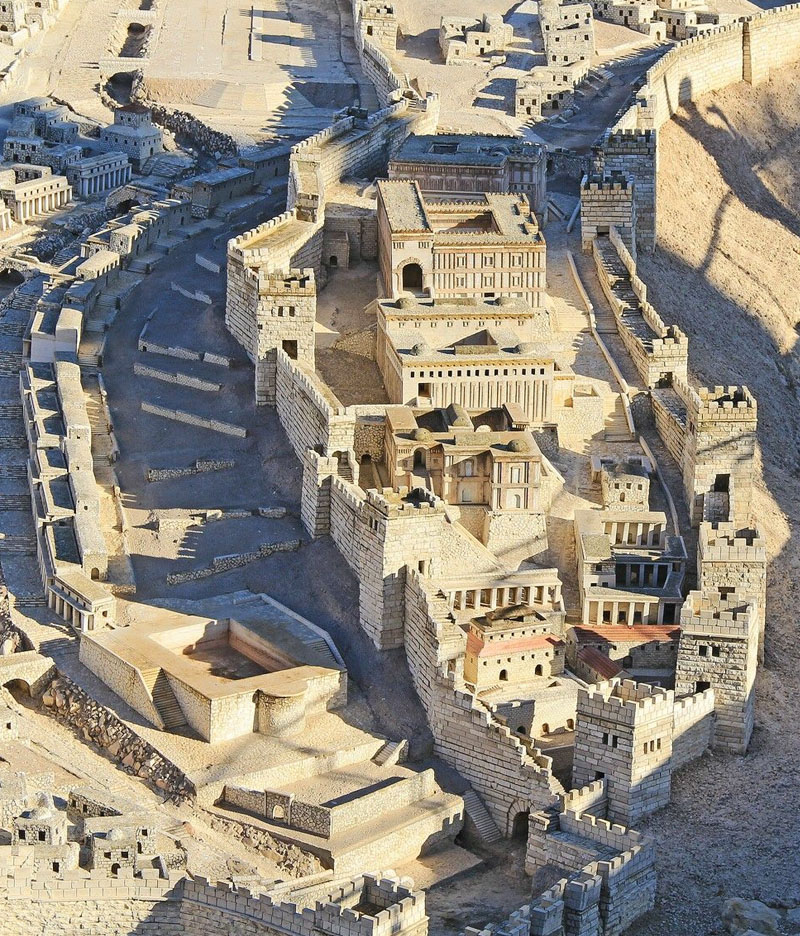

which opens under the citadel

the “mouth of Hell”

like a new sicilian Jerusalem

protected by an evil creature, Macigna

who used to leave the river which flows to the valley

just to drag into the abyss

those bold childs

that, to become adults,

dared to challenge that dragon from the canyon of Carapè”.

A passage to the underworld protected by the devil Macigna

There are places that speak and have no mouth, streets that tell stories without a narrator, views that enchant curious passersby…

That’s how Marco Fragale describes Gratteri in the opening of his poem – Quella viuzza del mio borgo (The alley of my village) – third place at the 2015 Edoardo Salemi international award. Never like this case, the name of a place in Gratteri could pass on ancient beliefs and folktales concerning linguistic and anthropologic areas about the village considered the most enigmatic in the Madonie. We are talking about a valley, among two mountain slopes, in the shape of a crater, suspended by godly hands, between burning rocks and the Etruscan Sea that covers up arcane legends of the most concealed Sicily. An ancient Madonian village, known for its beryl crystals, is set, like a diamond, into this authentic and natural terrace, 670 meters above the sea level.

A pleasant valley crossed by an icy stream, called Crati descends from Pizzo Dipilo, crosses the town until it flows down the Mulinello cliff, located in the districts of Conigliera and Minnulidda and cascades down to Mancipa. The village’s citizens call this cliff “ A vucca o nfiernu” that means “the Hellmouth”, because the folk fantasy states that there would be a passage to the underworld, just under the fortress in Madonie, like a Dante’s sicilian Jerusalem, defended by Macigna, an evil creature.

This is the popular belief, handed down over the centuries. Indeed, it affirms that this devil, which looks like a dragon, would suddenly come out of this cave to catch those brave youngsters, who performed the ritual of leaning too much from the cliff of the Carapè, in order to become adults.

Grandmothers told their youngest grandchildren, especially the lively and restless ones, this story, to keep them far from cliffs or streams. The intention was to make kids believe that the monster would have brought them with itself into the bowels of the earth or inside the wells, in the water.

The legend also says that for this reason in an immemorial time, the archangel San Michele was chosen to protect the village. Through his shining sword, he chases that beast back into the abyss. Even today, some pious women recite the following litany:

“San Michieli arcancilu oh risplendenti / Vui siti lu meru Ancilu di Diu / sutta lu pedi tiniti un serpenti / chidda è la spada chi vi detti Diu / Tiniti li volanzi giustamenti / pisati st’arma e purtatila a Diu”.

that is “ you, shining archangel Michele/ you are the God’s angel/ you have a snake under your feet/ that is the sword God gave you/ You keep the balances in a fair way/ weigh this weapon and take it to God.

Anyway, with regard to Macigna’s name, it could be meant as a variant of “ Macingu”, that from the ancient sicilian dialect would designate the devil. In this connection, M. Pasqualino wrote in his Sicilian vocabulary: “ Macingu, name that low social classes give to the devil, satanasso, satanas, diabolus”. Traina adds “perhaps from greek màchimos, pugnator, bellicoius (conspirator, demon) or eroded form coming from the latin malignus”.

Antonino Buttitta asserts that it should be linked to «all those beliefs, found among the most different populations, and which […] can be traced back to the same conception of a secret force operating in the universe and participating in the happening of the unusual». The anthropologist relates the meaning of the word “macignu” (< machineus) with the Melanesian concept of “mana”, namely “devil”, and with the Latin one of “numen”, which means “fate, unexpected event, destruction”.

Nevertheless, there is also another interpretation. A linguistic study about the lexicon of the Madonite dialectic culture, carried out by the University of Palermo, shows that the words “macignu”, “macingu” and “macinga” can be associated to the concept of a “strong swirling wind” and they can be found also in Bagheria, Petralia Sottana and Castelbuono.

However, the story about Gratteri would be a charming popular story that includes several meanings which could be dwelt on both from a linguistic and anthropological point of view.

For instance, in the tradition of Sicilian folklore there are many legendary monsters and mythological creatures with several characteristics similar to those of Macigna. These popular legends have been told, from time immemorial, in different parts of Sicily as in the case of “Sugghiu”, a mysterious monster with a frightening appearance that lives in the coastal areas and in the swamps of many villages and districts of the island.

Popular rumours tell us that the first sightings of the “Sugghiu” are dated back in 1800, the century in which the mysterious creature made numerous apparitions along the Tyrrhenian coast or in the municipalities of the Alcantara Valley, Brolo, Torre Archirafi and in the woods of Madonie (Debora Guglielmino, 2020).

This belief about the local Loch Ness monster is so deeply rooted in local folklore that it has even shaped some idioms and nicknames also in Gratteri. Just as Scotland has its infamous Loch Ness, so Sicily has its mysterious monsters.

In this respect, some young university scholars, passionate about the film genre “Moster”, have recently founded a specialized film magazine, which also dealt with the bestiaries of the Sicilian tradition. We report three meaningful examples of mythological creatures similar to Macigna and which are taken from the essay of Matteo Berta, Alessandro Sivieri and Giovanni Siclari, “La tradizione sicula con le sue creature mitologiche e mostri paurosi, 2020” (The Sicilian tradition with its mythological creatures and frightening monsters, 2020).

The Biddrina

The Biddrina is a mythical animal that is said to live in the wetlands of the countryside. Talking about it is very common in the province of Caltanissetta, in the southern part of Sicily. Many people sustain that the term Biddrina comes from the Arabic language and indicates a big aquatic snake. It is likely to be an enormous grass snake (at least 20 feet) with a head which looks like a bass drum and a coloration between green and blue. It should also have features of dragon and crocodile.

It is visible at night, especially because it has shining red eyes like lighthouses. It wanders around trees and reeds, eating goats, lambs and human beings. It drinks sulphurous water which flows near the mines and from this water it acquires strength and immunity to physical damages. According to the legend, a common grass snake becomes a Biddrina by magic, if it has been hiding itself for seven years.

The Marabbecca

From the abyss of Sicilian folklore, among the darkest shadows on earth, nestles the Marabbecca, a monstrous creature that sometimes looks like a woman and others like a monster that lives in wells and water tanks waiting for children and adults to fall into them.

The Marabbecca, a bogeyman invented by mothers in the rural world to try to keep their children away from the dangers of wells, also embodies the very fear of what we cannot see, of what our mind thinks is waiting for in the darkness (in this case the darkness of the ditches).

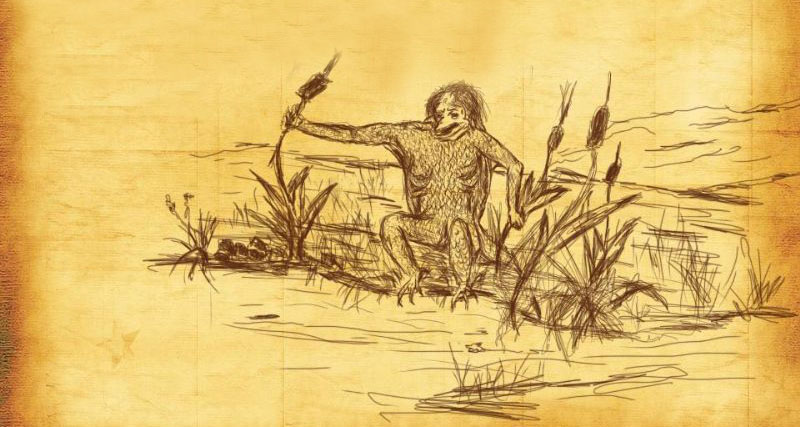

The sugghiu

In the case of Sugghiu we are not dealing with an elf or a strange animal, but a monster in the true sense of the term: it is a hybrid between a human being, a mammal and a reptile, about two meters long, with the body covered with greenish scales.

Its eyes are as fierce as those of a rabid dog. This legendary entity has also been sighted recently in various parts of Sicily, including forests, swamps and coastal locations. Since the early 1800s, traces of it have been found on the Tyrrhenian coast, in the Agrigento and Ragusa areas. Its repulsive appearance has made it the protagonist of joking insults and idioms.

Its call is no less disturbing and recalls both the grunt of a pig and the braying of a donkey. The monster would employ this sinister call to lure the other animals, which are then devoured with ferocity. Sugghiu’s stomach is in fact very resistant and allows him to digest even stones. Despite frequent encounters with humans, few have tried to tackle this sort of southern Chupacabra.

It seems that a hunter shot him so many times that he ran out of bullets from his rifle, but without causing him any visible damage. We can therefore deduce that the scales of his skin are very hard. Many farmers attribute the thefts of vegetables and cattle to Sugghiu.

Marco Fragale

(Università di Palermo)

Bibliography

Research and interviews have been done by Marco Fragale with the oldest citizens of Gratteri from 2002 to 2017. Buttitta A. (2011), Macingu, numen, mana, in Gruppo di ricerca dell’Atlante Linguistico della Sicilia (a cura del) (2011), Per i linguisti del nuovo millennio. Scritti in onore di Giovanni Ruffino, Palermo, Centro di studi filologici e linguistici siciliani, pp. 248-257.

Sottile R., Genchi M. (2011), Lessico della cultura dialettale delle Madonie. 2. Voci di saggio, Palermo, Centro di studi filologici e linguistici siciliani). Sottile R., I nomi dei venti in Sicilia tra toponomastica, geomorfologia e “mondo magico”. Possibili itinerari di ricerca – Università degli Studi di Palermo.

Pingback: Gratteri: the most mysterious village of the Madonie - Sicily on Horseback