Your basket is currently empty!

The oracle of the old woman in the cave

For generations, the inhabitants of the medieval village of Gratteri have handed down millenary beliefs and fanciful legends of what today is to be considered the most authentic but, at the same time, oblivious history of Sicily.

This could be the case of a thousand-year-old myth, the one of an inhuman Old lady who would reside alone in the depths of a mysterious cave, called Grattàra, which dominates the ancient Madonite village from above.

Trying to understand the origin of the myth, it would probably be necessary to analyze the symbolic meaning that could have assumed in the peoples of the past, the presence of a legendary woman guardian of the secrets of a cave.

In old times, many places in Sicily gained the reputation of dispense oracles, especially caves, very often ancient places of worship of indigenous gods and oracular sites, such as the one of the sibyl lilybetana.

As explained in fact, the Sicilian scholar Giovanni Teresi – in his historical research on the cave of the Sibilla Cumana in Marsala – caves and ravines, natural ditches and small dark chasms, became in Sicily places of religious worship, leading to the underworld, and in them could reside only underground gods.

Thus, in the indigenous religious conception, the divine entities were often even underground gods connected to the earth as Chtonie divinities; dark garrisons both of life and death, vegetation and the underworld, which in many places were identified with Demeter and Core (G. Teresi, La grotta della sibilla lilybetana, storie di folklore e tradizioni popolari, 2018).

For such considerations, therefore, it would not be completely out of place, as we will see later, to be able to link the legendary presence of an old hermit, dweller of the Cave, to a primordial sibyl, dispenser of oracles through the source of the Nymph, the indigenous deity of the mountain.

With the word “Sibyl” the ancient Greeks and Latins referred to a figure who existed historically, identifiable with the whole class of prophetesses, virgin and young women, sometimes considered as decrepit, who lived in caves in different places in the Mediterranean basin.

They performed mantic activity in a state of trance inspired by a god (usually Apollo) able to provide answers and make predictions. The will of the gods, was dispensed in various ways: with signs on the entrails of sacrificial victims, with the movements of objects thrown into a source, through the flocking of the branches of a sacred tree, or through the mouth of a human being, as in the case of the oracle of Delphi, in Greece.

Very often, these prophetesses drank water from a spring or a well which, due to their exalted imagination, led to a state of intoxication. Specifically, with regard to the case of the Sicilian Sibyl, which Teresi himself located near Lilybeo, anthropological studies clarify that she had the characteristics of a priestess who asked for her answers to another deity, the nymph of a spring (See historical research by G.Teresi, online).

That’s probably why the presence in Gratteri of a cave, a millenary old one, and a source called “of the Nymph” (similar to the source of the Grattara cave), could be considerable elements to support the mere conjecture of an original oracular site.

Over the centuries, however, the myth of a long-time prophetess would be transformed into another legend, still known today in the village, the legend of the Old Hag.

As the gratterese legend says, since the beginning of time, A Vecchia, a woman as long-lived as ugly, would watch over the ancient Madonite village from the top of her cave, spending every single day of the year preparing gifts and goodies for the children of Gratteri.

The “Strina” would come down to the village only on the last night of the year to give her gifts to those children on the basis of their merits, sneaking silently from the most unthinkable places of those humble dwellings. She knows everything about those children, to the point where, throughout the year, their parents encourage the little ones to behave diligently, to avoid the nasty surprise of finding only ashes and coal:

“Pi Natali nasci u Bammineddu,

u primu di l’annu veni la Strina”. (Antonina Lazzara, classe 1923, intervista 2007).

(For Christmas the Child is born,

the first of the year comes the Strina.)

“Jnnaru mina ventu e fa furtura,

‘u primu jornu ti scontra la Strina,

si nni cala adasciu adasciu a la piduna

e vvà circannu risiettu di marina”. (Giuseppa Lanza, classe 1922, intervista 2010).

(January sowing wind and brings frost,

the first day you meet the Strina,

walk down on foot, slowly

to look for the mild climate of the coast).

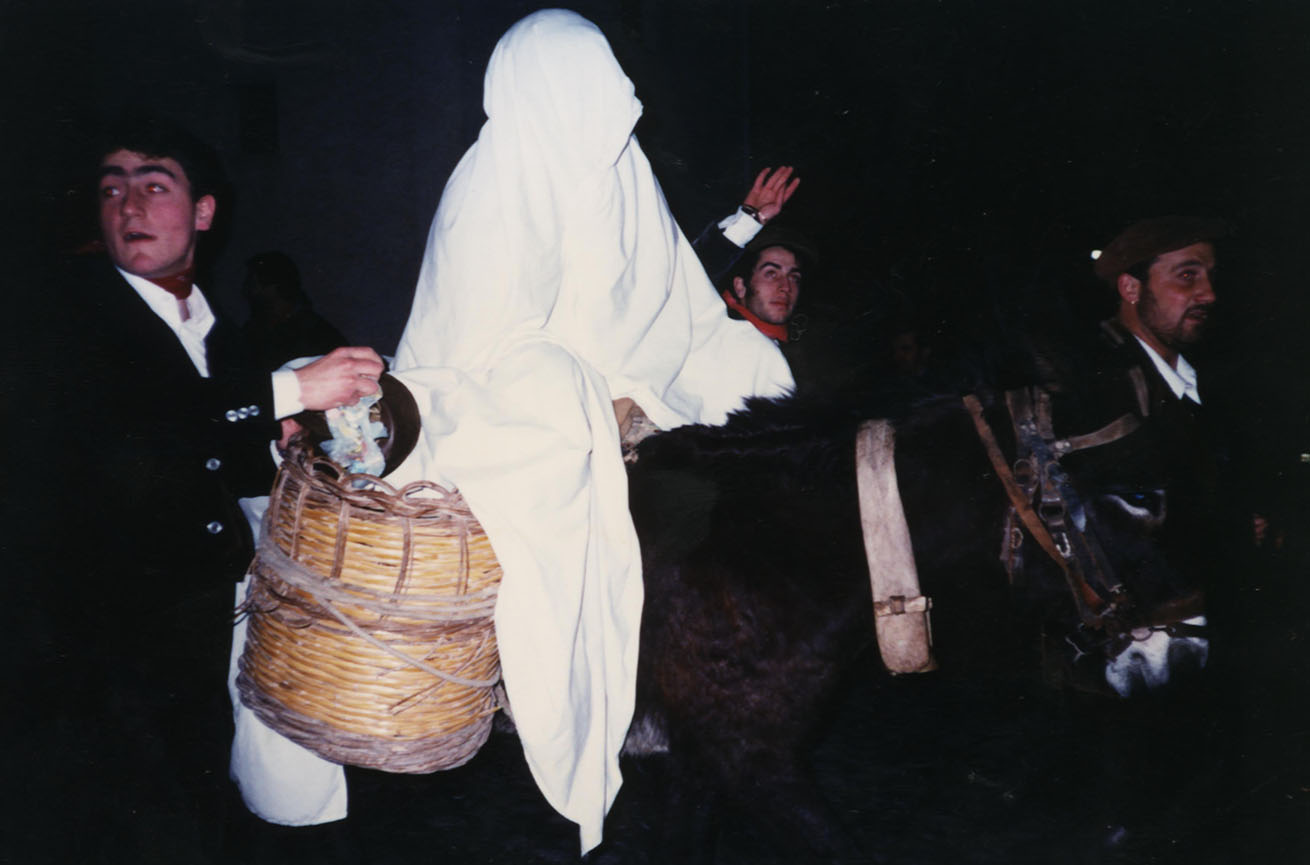

In the past, as the elders tell, a significant New Year’s Eve rite was performed in the village on the last day of the year. In fact, as Mrs. Giuseppa Ilardo explains, a masked man – the Old Lady – passed through the streets of the village on the back of a donkey, hiding his face under a white sheet, escorted by the boys of the village who announced, with their screams, his arrival: “To Vecchia! U picciriddu mi cianci!”.

They were conducting an itinerant quest through the streets of the village, playing animal horns, whistling, and singing from door to door:

“O mi dati un turtigliuni, o vi scassu lu purtuni! O mi dati un cucciddatu o vostru maritu vi cadi malatu!” (Give me a turtigliuni or I break your door, Give me a cucciddatu or your husband get sick).

So, every family offered what they could: dried figs, broad beans and Christmas sweets – the traditional “turtigliuna” or “cucciddatu” – candied peeled and covered with sugar tails, called “diavulicchi” in Gratteri. This offer was reciprocated with an exchange of greetings, for a prosperous and fruitful new year:

“Buon Capudannu, buon capu di misi,

li turtigliuna unni l’aviti misi,

l’aviti misi nte la cascitedda,

niscitili ca passa a Vicchiaredda”

(Happy new year, of the months the leader,

Are there turtigliuna in the hamper?

Put them on the street,

The Old Lady will pass on feet)

(Maria Antonina Cirincione, classe 1913, intervista 2007).

According to the anthropologists of the University of Palermo, this ancient custom, like others in Sicily, would be of extraordinary anthropological interest, since it would be linked to the ancient ritual exchange of gifts, masks and rites of transition during the winter period to refound the cycle of the year and with it the very life of the community.

As Ignazio Buttitta explains “it is not by coincidence that the poor and the children receive gifts on specific ritual occasions, nor that in critical periods, masked groups break into the living space and go to the houses and farms to collect gifts […].

Life depends more than ever on the dead, on the ancestors, after the winter has passed. From them, who in this period of low light and cold find opportunities to wander the earth’s surface, it is necessary to protect themselves; it is necessary to make them propitious by offering food and warmth; it is necessary to keep them at a distance by lighting fires, producing deafening noises (A.Buttitta 2006, pp.110-114).

From the 70’s to the present day, this ancient custom has been taken up and adapted by the “pro-loco” in a folkloristic way. So, in the night of New Year’s Eve, at 9p.m., the Old Lady is welcomed by the people in the district of San Vito.

She, because of the tradition, is covered by a white sheet, on the back of a donkey, supported by a procession of boys dressed like ancient shepherds and illuminate the path with rudimentary wax flashlights, screaming her name at the top of their voices, playing horns of animals and cowbells.

As Buttitta himself observes, the noises and sounds of the cowbells would be “otherness indicators”. The Old Lady, after a whole year locked up in the cave, comes back down to the village greeted with joy by the whole community (A.Buttitta 2006). In this way, it breaks the peace of the night with a masking even sound.

And it is precisely the Carusi (children) the main protagonists of this tradition, dressed in traditional costumes of shepherds and mountaineers: pants and velvet jacket, hooded cloak, “scappularu or tistièr” (a vest), coppola (the sicilian traditional hat), handkerchief around the neck, leather leggings “jammalina”.

It is on them that we must focus attention, because at first glance another ritual could go unnoticed, the one of initiation the carusi perform during the coldest night of the year, getting ready to grow up.

From the age of seven, in fact, the children, very often entrusted to the older ones, walk together with a group of boys along the winding path that climbs through the pine forest of San Vito to the Grotta Grattara.

A test of courage and solidarity: to overcome the fear of the darkness of the night and resist those verses, like the wind howling through the trees, like mysterious presences of nature spirits in a fairytale fantasy.

Once you arrive at the cave, you return to see the stars again. Thus, the most experienced of the group plays an ox horn screaming in the cave. A sound so vigorous that it spread to the village, in the peace and quiet of the night. It is the voice of the Old Lady, ready to come back among her people. The test is passed. The boys return down, but this time with lit flashlights guiding their steps.

The Carusi, repeating these gestures in an unconscious way, only reaffirm the identity of the group, the sense of belonging to the community, seen as a way of preserving social memory.

As the anthropologist Sergio Bonazinga argues, the masking of the boys would also be sound; each child, in fact, has its own cowbell, a beeper, as in a flock.

The cowbells, as Schmirtt claims, should be associated with animals and not to humans, and in turn, to the ancestors of the group. Therefore, children play an important role as mythical mediators between the world of the dead and the world of the living, since they enjoy a special status and are responsible for ritually propitiating the orderly cycle of the seasons (Schmitt 1988, p.146).

In any case, the advent of the masks, indicating the necessity of death, imposes the return to life. The mask of the Old Lady is insulted, mocked, both for its longevity and for its ugliness, as is reported in the popular songs adapted by the “pro-loco” on the paradoxes of the Pitrè:

“Facciazza d’un crivazzu arripizzatu…spaddazzi di na mula di trappitu…taliàti genti tutti a Santu Vitu…niscìu la Vecchia ncerca di lu zitu…”. In this way, extraordinary events would be evoked like the birth of the Old Lady:

“Quannu nascisti tu làdia vicchiazza…ci foru centu negli e trimulizzi…lu suli s’annigliò cu nna nigliazza…Lu risìnu cadìa stizzi stizzi”. During this night, we would have the re-actualization of the myth, just as extraordinary events oncr took place, so for one night the balance is broken with the repetition of events; with its arrival, the reversal arises, the otherness of the natural balance: “Vitti affacciari lu suli di notti…e quattru muti jucari a li carti…iò vitti siminari favi cotti…si vitturu ntè marzu ficu fatti…”.

An itinerant questua takes place, a ceremonial circuit of exchange, animated by band sounds, folk songs and Christmas carols. Hilarity and joy take over. In order to entertain the public, the “scecca” is danced in the small squares and from time to time wine and liquors are made to keep it a bit ‘on top. Alberto Maria Cirese, revealed the fact that: the “strenne” of New Year’s Eve are an evident case of total desecration. They were long condemned as devilish and pagan, along with other customs of the Calends of January, but these tenaciously resisted the prohibitions even though they were largely losing those ancient functions.

The ancient pagan sacredness, reconfigured as a new Christian sacredness, the New Year’s Eve, lost its ancient superstitious values, could be reconsecrated (Cirese 1997 p.126-127). On this occasion, at Gratteri, Christmas presents are postponed, gifts for children are hidden in the most curious and unimaginable corners of the house; it is the Old Lady who has hastily hidden them, sneaking in through some crack. To do this, however, the little ones have been sent to bed early; for them, sleep at a certain hour is a must, and woe betide them to wake up, because if the Old Lady were discovered, she would carry out her revenge: to pierce the eyes of the curious.

The figure of the Old Lady represents a scapegoat, to her is attributed all the faults of the community, is publicly mocked “Vecchia Befana brutta, Vecchia Befana, nesci sta sira, nesci di ntè sta tana…” and again “Avi n’annata sana chi sini n’chiusa, grabba la scecca e scinni n’cerca di fusa… Vecchia Vicchiazza brutta, Vecchia Vicchiazza, scinni sta sira, scinni nta nostra chiazza…. E nun ti mariti nò, schietta arristari tiròllallalla… “.

The Old Lady, however, after having distributed her gifts, must necessarily return to her cave and stay there for the whole year, so that the broken balance can be restored with the beginning of a new and fruitful year.

“Ci sunnu i patri pronti cu li vastuna, s’on lassi e picciriddi li tùrtigliuna…“L’occhi ti sgrifamu Vicchiazza brutta, s’on scarghi u sceccu e torni a la tò rutta…”.

Today the parade of the event ends in the main square where some young people entertain the inhabitants and tourists with the “Vanniata di festiviata di l’annu”, the process of events that happened during the year. With irony and sarcasm is made the parody of the facts and the local and national characters that during the year have made talk about themselves.

At the stroke of midnight, then, we welcome the New Year with a collective toast, with the distribution of typical sweets and the burning of a straw dummy representing “the old year”, between firecracker shots and fireworks.

The puppet that the boys dressed like a man, brought by the boys during the tour of the village, is punched and eventually hanged and burned as a scapegoat. Buttitta observes: the fire and the burning of puppets, mark with their presence, on the one hand the elimination of time consumed, on the other the opening of a new time; for this reason these signs can be traced back to rites of passage to refound the cycle of the year and with it the very life of the community” (Buttitta 1984, p.137).

In the puppet who dies at the stake, the faults accumulated by society are destroyed, faults that men could not have failed to commit, since every act performed on nature and its order is in any case a sacrilegious violence.

The ultimate purpose of all these winter rites could therefore be the destruction of the consumed time, of which the puppet is a symbol (Buttitta 2002, pp. 136-137).

The event not only involves visitors but also the entire population who participate in the songs and dances that are held until the stroke of midnight; a privileged moment of socialization and strengthening of the sense of belonging to the community.

Text taken from M.Fragale’s thesis “The cycle of the year at Gratteri. Devotional aspects and anthropological significance”, University of Palermo – A.A. 2006/07.

Viva, viva lu Capudannu

Rit: Viva , viva lu Capudannu

senza lastimi e senza affannu.

Viva, viva lu Capudannu

allegria pi tuttu l’annu.

Grattalusci chi siti in risbigliu

ascutati stu nostru cunsigliu

pi sta sira manciati e biviti

ca dumani aluvoti nun ci siti. Rit...

Picciriddi chi stati durmennu

di nto lettu scinniti currennu

chista è l’ultima notti di l’annu

c’è la Vecchia chi vvà passannu. Rit…

Vi viviti un bicchieri di vinu

vi quàdia e vi nforza lu schinu

cinni dati un bicchieri a zza Nina

ca travaglia sira e matina. Rit…

E passannu di sutta u palazzu

senti sempri nu granni fitazzu

e cc’è genti chi ddà nun ci camina

ca si scanta di la china. Rit…

U sapiti cari paisani

c’ò macellu scannunu i cani

e i viteddi ditti di latti

nun sunnu autru chi carni di jàtti Rit…

A menzannuotti viniti nta chiazza

ci sarà nna ranni fistazza

a la genti chi va sparrannu

ci vanniamu li festi di l’annu. Rit…

Quannu nascisti tu

Quannu nascisti tu làdia Vicchiazza…

Ci foru centu negli e trimulizzi…

Lu suli s’annigliò cu nna nigliazza…

Lu risinu cadìa stizzi stizzi…

Rit: E nun ti mariti nò

nun ti mariti nò

e nun ti mariti nò

schietta arristari tiròllallalla…

Facciazza d’un crivazzu arripizzatu…

spaddazzi di na mula di trappitu…

taliàti genti tutti a Santu Vitu…

niscìu la Vecchia ncerca di lu zitu…

Rit…

Vitti affacciari lu suli di notti…

e quattru muti jucari a li carti…

iò vitti siminari favi cotti…

si vitturu ntè Marzu ficu fatti…

Rit…

Aricchi surdi e cantuneri muti…

speramu ca nun lu sannu i Lascaroti…

la Vecchia vvà spartennu cosi duci…

si voli fari amici i Grattalusci…

Rit…

Vecchia befana

Vecchia Befana brutta, vecchia Befana,

nesci sta sira, nesci di ntè sta tana……

Vecchia vicchiazza brutta, vecchia vicchiazza, scinni sta sira, scinni nta nostra chiazza……

Avi n’annata sana chi sini n’chiusa, piglia la scecca e scinni

n’cerca di fusa……

Prima chi tu scinni, jttannu vuci,

piglia lu saccu chinu di cosi duci….

Quannu tu arriverai ntè stu paisi,

furria casi casi purù p’un misi……

Ci sunnu i patri pronti cu li vastuna

s’on lassi e picciriddi li tùrtigliuna……

L’occhi ti sgrifamu vicchiazza brutta,

s’on scarghi u sceccu e torni

a la tò rutta…..

Marco Fragale

(Università di Palermo)

BIBLIOGRAFIA

BONAZINGA SERGIO, Tradizioni Musicali in Sicilia. Centro di Studi filologici e linguistici siciliani, Palermo 1995

BONAZINGA SERGIO, Forme sonore e spazio simbolico. Tradizioni Musicali in Sicilia, materiali per il corso di etnomusicologia dell’Università di Palermo, 2009.

BUTTITTA ANTONINO, L’utopia del Carnevale, Palermo, 1984

BUTTITTA IGNAZIO EMANUELE, I morti e il grano. Tempi del lavoro e ritmi della festa, Roma, Meltemi, 2006a.

BUTTITTA IGNAZIO EMANUELE, Il fuoco sacro. Simbolismo e pratiche rituali, Palermo, Sellerio Editore, 2002a.

CIRESE ALBERTO MARIA, Dislivelli di cultura ed altri discorsi inattuali, Roma, 1997.

GIALLOMBARDO FATIMA, Le Vecchie di Natale, in “La Sicilia ricercata”, I/2, pp. 39-43. 1999b

LéVI-STRAUSS CLAUDE, Babbo Natale giustiziato, introduzione di ANTONINO BUTTITTA, Palermo, Sellerio Editore, 1995.

SCHMITT JEAN CLAUDE, Religione Folklore e Società nell’Occidente Medievale, Laterza 1988

TERESI GIOVANNI, La grotta della sibilla lilybetana storie di folklore e tradizioni popolari, 2018 in www.culturelite.com

Pingback: Gratteri: to discover the hidden treasure - Incao Holiday