Your basket is currently empty!

The Holy Week. A Sulità

A sulità

The Holy Week is rich in religious traditions, which began on Palm Sunday, with the symbolic act of tying the bells, replaced by rudimentary wooden instruments, the “truòcculi“, who hang around the streets of the town. In every church during Holy Week in the past devotional songs in dialect and prayers were recited which even today older women also pass on in the form of lullabies.

Speaking of particular days for fasting, some women, every Saturday, and in particular Holy Saturday, recite a prayer fasting to Our Lady, to obtain seven years of grace and indulgence:

“Matri celesti celi, c’era ‘na missa cantata, una chi si dicìa ‘natra chi niscìa, dda intra c’era la Vergini Maria chi si la vidìa. Passò lu sò caru Figliu e cci dissi: ‘Matri chi faciti duocu? Vui aviti durmutu, iò haiu

patutu! e ccu lu dici a lu sabutu a diunu avi sett’anni di razii e di pirdunu”.

Significant is the fact that the death and resurrection of Christ took place in the past in Gratteri respectively on Thursday and Holy Saturday at noon. In fact, on Thursday the traditional mass of the washing of the feet was held, which was called “missa siccàgna” precisely because the Eucharist was not celebrated.

One of the most typical customs by now fallen into disuse was also to set up sepulchers in the various churches by darkening the windows and covering the altars with dark curtains. At the center of each church, under the altar, a sepulcher was set up, adorned with calla lilies and wallflowers “u bàlicu” and with containers of wine boiled on braziers to release a pungent and acrid perfume.

Furthermore, the traditional “laurièddi”, dishes made of wheat seeds, lentils and broad beans, which were put to germinate in the dark during the previous weeks, could not be missing. The tombs were watched over by two brothers in turn. On the evening of Holy Thursday all the brothers – called “fratielli o babbuini” – went to visit the tombs with a characteristic medieval costume. They wore a white cape, a crown of thorns on their heads – “cinturieddi” – and a rope of ampelodesma, – a “ddisa” – tied around the neck with a slipknot, called “a pastùra”.

The brothers set out from their seats in single file, led by the brother drummer while they all sang together traditional complaints and songs also in Latin as evidenced by the Chapters of the brotherhood of Carmel of 1874: “Il Giovedì Santo la sera, circa alle ore 22 si riuniranno tutti i confrati nell’oratorio, i quali adorni di libàno e corona di spine, di unita al Cappellano anderanno a visitare i sepolcri. Nel corso del camino canteranno con interruzione il ‘Miserere’ […]”.

As the older confreres explain, only the Confraternity of the Rosary, as the most grieved, performed this rite late at night, as a sign of mourning. These, on Easter day, entered the church in a row, led by the brother drummer who played dead, with the visor covering his face and which they raised only at the time of the Eucharist. Then, at the end of the Easter celebration, they left the church with their faces uncovered with a festive roll.

For some years the custom of the deposition of Jesus from the Cross has been reintroduced. In the past, the superior of the confraternity of the Sacrament, helped by other confreres, performed this symbolic rite. The image of the Crucifix with the joints of the articulated arms was detached from the cross and lovingly placed in the urn. Later, it was prepared for the funeral procession, while women sang suggestive traditional songs. Moving is the one remembered by the older women, who in their day was sung in the church of the Old Matrix:

“Gesù vi vìu ‘ncruci chi languìti a causa di li miei gravi piccati, iò sugnu un piccaturi e Vui patìti, iò sugnu dibituri e Vui pagati. Maria Matri d’amuri a nui vulgìti u’ sguardu piatusu e ‘ni salvati”

In this church, in fact, a good number of elderly women sing, kneeling on the pews, the Rosary of the Addolorata, a sort of chant in dialect, rattling off the beads of the Rosary for seventy times, followed by a particular song of the Creed, ‘U Criedu Romanu”, and from Salve Regina all’Addolorata in dialect. For each grain we match:

“E decimilia voti e sia lodata la bedda Matri Maria l’Addulurata”

“l’Addulurata ‘Gnura, Crucifissu e Maria nostra Signura”.

In addition, the tens are added to each end:

“Siemu junti à la (dicina) ppi ludari a ‘sta Rigina, la Rigina di setti dulura ‘ntesta purtava la Santa Cruna, la Rigina Addulurata ‘mpettu purtava la Santa Spata”.

Remember that the number seven is sacred in the Christian tradition: in fact, there are seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, seven deadly sins, like seven daggers that afflict the heart of the Madonna. In the past, even the simulacrum of the Addolorata was prepared for the occasion, setting up a pitiful image of the seated Madonna consisting of a cloth habit on which the hands and wooden head were grafted and totally decorated with a black mantle and a white handkerchief in his hands, which trembled during the procession, impressing the faithful.

An interesting aspect has it that the brotherhoods depart from different points of the town and meet near the Old Matrice, where the complete funeral procession takes place. Each of them carries its “mystery” in procession, that is, the image inherent in the Passion of Christ.

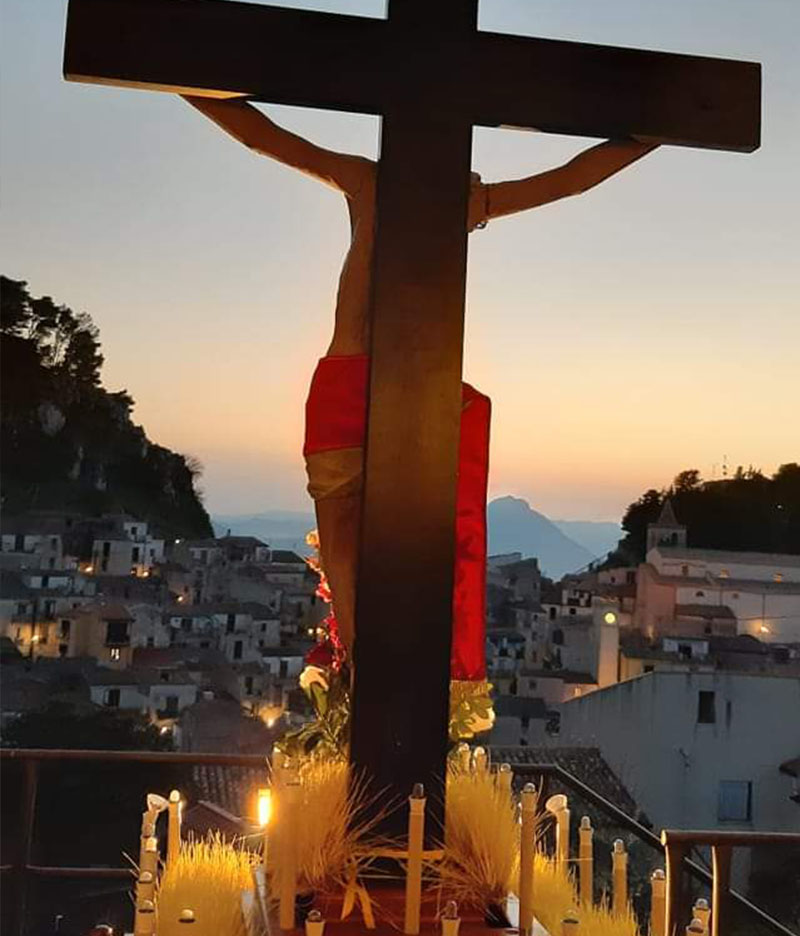

From the Church of Sant’Andrea and the Matrice Vecchia, around 8:30 pm, the drummers, standing at the door of the church door, in a strategic position, begin to beat an ancient animal skin drum, with a typical cadenza a morte, a roll so vigorous that it echoes throughout the town and creates a sad, heartfelt atmosphere. Around 9.00 pm, the members of the brotherhood of the Madonna del Carmelo from the church of Sant’Andrea begin to set out in single file towards Piazzetta Garibaldi bearing the image of the SS. Crucifix.

The palanquin is carried by hand by the same brethren who wear the traditional habit of the Carmelites: burgundy tunic, with cord and white cape that goes down to the hips. They hold in their hands chains with big bronze rings, which they shake quickly to recall the instruments of the flagellation of Christ.

In the past, as the elders explain, all the brethren of the funeral procession used them to beat on the shoulder or on the chest, as did the ancient flagellants in their penitential processions. Therefore, it is the members of the confraternities who perform this public function as narrators-actors of the drama.

The Saints Niriani complain along the way to the lower part of the village where, at the Church of San Giacomo, will take place the first meeting with the homonymous brotherhood, which carries in procession the image with another mystery. From the latter church the pitiful image of Ecce Homo. Jesus’ half-brother, crowned with thorns, bears the vivid signs of flagellation: his face full of bruises and dripping with blood, characterized by a dramatic expressiveness and full of pathos, a red cloak over the shoulders that lets glimpse a bleeding wound from the chest with his hands tied by ropes and a reed under his arm.

The small vara of Ecce Homo is decorated with red carnations, violets, bàlicu, evergreen and laurel fronds, and six lamps, with quadrangular coating of red tissue paper, “u cuoppu”. The vara is carried by hand to the height of a man by four hooded men to remember the soldiers who accompanied Jesus to the gallows.

For a few years now, two other mysteries have come to the procession from the nearby Church of San Sebastiano: Christ flogged at the column and Jesus carrying the cross, brought by the sisters of the Holy Thorns. As the older women say, in the past in Gratteri, all the simulacra related to the passion of Christ present in the different votive aedicules of the country were brought for the funeral procession. The procession opened the image of Saint Michael the Archangel holding in his hand the pyx, symbol of the passion; the Angel who appeared to console Jesus in the garden of Gethsemane.

The procession of Good Friday is called to Gratteri in Sulità, because, according to local tradition, the brethren parade one after the other in solitude as the rite that took place in 1600 in Seville, the Soledad, from the typical process of the salmodianti brethren, in single file – instead of arranged in two rows as in the other processions – dressed in a penitential sack and holding a flambò or a lantern (Scelsi 1981, p.121). From the statute of the confraternity of San Giacomo dating back to 1881, we read:

“every confrere must dress the sack, visor and cloak. The white bag symbolizes the whiteness of the costumes, the visor indicates humility and the cloak charity in pitying the defects of the neighbour and helping him in his needs”.

The procession crosses via Fiume and proceeds towards the upper part of the village, while a large group of women in the Sant’Andrea district, chant a traditional funeral lament: “Lu Vènniri Santissimu”. The theme of the lament is “the search”, or the search for Jesus by Our Lady and Saint John. A song of sorrow that of Mary, seeing her son scourged; the encounter with the blacksmith and the anguish of Our Lady for the death of her Son, who asks the people to be brought a black mantle. Similar songs in the past, were used in Gratteri also as nenias, to make the little ones fall asleep.

At Salita Orologio, the procession divides again. The confraternities with their simulacra take a narrow alley to get to the church, while the Crucifix and the crowd go to Piazzetta Garibaldi to wait for the encounter with all the mysteries. After a long row of brethren, the ecclesial authorities leave, followed by the urn, carried on the shoulder by eight brethren wearing the characteristic medieval costume: tunic and white hood, purple cloak.

A very significant moment is the exit of the urn from the “dammuso”, what was once one of the accesses to the ancient castle. Complete silence. Following the litter parade solitary brotherhood of Our Lady of the Rosary, with the black scapular, followed by the image of Our Lady of Sorrows, carried in procession by hand by four girls, entirely dressed in black holding the chains. The three superiors of the Confraternity of the Rosary close.

A devotional aspect is also the place of the image of Our Lady of Sorrows behind the band and in the crowd. In fact, as the faithful explain, tradition wants the Mother to be in search of the Son. The same word Sulità, (loneliness, melancholy) is to refer to Mary left alone. In the past, dressing in black like Our Lady of Sorrows and being close to her behind the procession was a devotional aspect of the request for a pardon.

It is the people who, like Saint John, gather around Our Lady to console her, in a very warm hug. A highly evocative moment can be reached when the procession enters Corso Umberto. Once the city lights out, the only glare that can be glimpsed is that of the candles of the brethren and of the simulacri, in an atmosphere of other times. Behind the mysteries, the notes of the funeral march infuse the faithful with a vivid sense of sadness, so that the procession proceeds slowly, solemnly, collected.

At the arrival of the procession in the Mother Church, there is the preaching performed by the preacher father who goes directly to the pulpit. Then comes the solemn blessing, with the relic of the Sacred Wood of the Cross, while a pressing noise is heard, for the agitation of the crackles and chains. At its end, the procession starts again towards the exit of the church, and departs towards the stretch of Corso Umberto, up to the Church of San Sebastiano, where the final greeting of the Mysteries takes place, which are brought back to their respective churches.

The rites of Holy Week conclude the night of Easter with “a calata du tiluni”: a large tent of damascus is made to descend, to show everyone the image of the Risen One. The popular suggestion was that, if the large canvas had fallen straight down, it would have been the wish of a good agricultural year.

Women are responsible for the preparation of the typical Easter sweets – the “pupi ccu l’ova” – with different shapes: doves, baskets, horses, hearts. They are produced with sweet pasta embellished with a veiled of sugar and the colorful diavulicchi, very often with a boiled egg on top. Even the presence of diavulicchi is not less significant. They, in fact, allude to the evil that is always alert, but that is defeated year after year by the triumph of good.

Canto tradizionale del Venerdì Santo

(intonata durante il percorso del Crocifisso dalla Chiesa di Sant’Andrea a Piazzetta Garibaldi)

Oggi ch’è lu Vènniri Santissimu

la Matri Santa si misi ‘ncamminu,

ci scontra San Giuvanni pi la via,

ci dissi: “aunni iti, o Matri mia”.

E aunni vogliu iri, o Giuvanni

Iò cercu a me figliu Nazarenu;

vaiti ‘nte la casa di Pilatu

ca lu truvati tuttu flagillatu.

Tùppi tùppi! Cu è nte stu purtùni?

Rapìti ch’è la vostra Santa Matri!

O Matri Santa nun pòzzu rapìri

sugnu ‘nchiuvatu cu ferri e catini.

O figliu, anni mittìsti i tò capiddi?

Matri, nun l’haiu cchiù mi li scipparu!

E se sapissi quantu ‘ngrati fuoru,

ca pi capiddi spini mi mittieru!

Vaìti anni lu mastru di li chiòva,

faciti fari tri chiòva pi mìa,

nun li faciti né grossi nè fini,

c’hannu a passari sti carni divini!

Arrispunnieru li malaffattura:

gruòssi e pungiènti li sapiemu fari!

La Matri Santa sienti stu parrari,

scurò lu cielu, la tierra e lu mari!

Chiamàtimi a Giuvanni ca lu vogliu

quantu m’aiuta a chiànciri a me Figliu!

Di nivuru purtatimi u cummògliu,

ca iò pirdìvi lu mè caru Figliu!

Ora ca è muortu lu mè caru Figliu

ti benedicu li stinti e li affanni!

Li nuòvi mìsi chi ‘nventri ti tinni,

lu latti chi ti dètti Amùri ranni!

“Criedu Romanu”

Iò criu di l’Apostili

quannu a lu munnu ‘nsignaru

chiddu chi sacciu iò

lu ‘nsignu all’atri.

Iò criu a lu Diu Patri

e a Cristu cridiràu,

unicu figliu sò, nostru Signuri.

È granni lu sò amuri

e lu sò affettu tantu,

cridu a lu Spiritu Santu

e s’incarnàu.

Da Maria nasciu, Maria lu generàu

l’ura quannu aggh’juncìu

a Bettilemmi

e ddi Gerusalemmi patiu sutta Pilatu,

fui ncruci e fui ‘nchiuvatu

e sibbellutu.

A lu limbu è scinnutu

a nnì stannu l’abiati

ccu sò Patri assittatu

a manu ritta.

Judici di minnitta

li boni nati a dari,

li mali avi a castiàri

oh eternu chiantu.

Criu a lu Spiritu Santu

la Santa Chiesa Cattolica

Rumana e Apostolica,

nui cci cridemu.

Dimica vinemu

spartenza e opiri boni

e cc’è la cumunioni

o di li Santi,

e ccu ‘na fidi e tanti

e ccu ‘na spranza eterna,

criu a la vita eterna e cusì sia.

‘Stu creddu c’avemu dittu,

‘stu creddu c’avemu cantatu,

la passioni e morti ha prisintatu,

Viva lu nostru Diu Sacramintatu

Viva lu nostru Diu Sacramintatu.

“Salve Regina alla Madonna Addolorata”

Dio Vi salvi, Regina

e Matri Addulurata

Vi sia raccumannata

‘st’arma mia.

‘Sta razia vurria

di ‘stu me cori ‘ngratu

ferutu e trapassatu

a la me spata.

La mia vita è passata

tra tanti ‘ran piccati

pi grazia priati

a vostru Figliu.

A nui dati cunsigliu

lu stissu cunsigliari

chianciennu a lacrimari

li me erruri.

‘Stu cori chi duluri

spizzatimillu Vui

piccari ‘un vogliu cchiù

chiuttostu morti.

A nui ‘st’arma purtati

‘ncielu gluriusu

oh Matri piatusa eternamenti.

E poi divotamenti

gridannu quannu arriva

viva la Matri viva Addulurata.

Salve Regina Addulurata

Dio vi salvi, Regina

e Matri Addulurata

Vui ‘mpettu la purtati

la vostra spata.

Lu vostru caru Figliu

la cruci s’abbrazzàu

e addossu la purtàu

supra li spaddi.

O Figliu miu ‘nnuccenti

Tu comu l’hai a suffriri

ca pi li peccaturi

a ghiri a patiri.

O dulurusa Matri

Nun n’haiu chi vi fari

Ca di li piccatura

m’ha ‘ffari amari.

O Figliu giustu e santu

Tu a chistu nun pinsàri

ca di li piccaturi

Ti fazzu amari.

O Dulurata Matri

lassatiminni iri

ca s’avvicina l’ura

di lu me patìri.

Figliu tu ti ‘ni vai

mi lassi negli affanni

pi cunfortu mi lassi

a San Giuvanni.

Partemini Giuvanni

videmu unn’amu a ghiri

ca pi li scarbi

o ‘scuru am’a partìri.

Addulurata Matri

‘un haiu chi vi fari

ca lu Munti Calvariu

A ghiri a truvari.

S’ avvicina Maria

cu dulurusa vuci

ca pi li peccatura mè Figliu è misu ‘ncruci

O avari peccatura

chi cuori duru aviti

guardati a lu me Figliu

e nun chianciti.

Quannu lu misiru ‘ncruci

acqua ci addumannau

appi fieli e acitu

e trapassàu.

E prima di murìri

L’uocchi ‘ncielu alzàu

e ppi aiutu chiamàu

l’Eternu Patri

Figliu nun ti partiri

ca su l’ultimi uri

e t’innacchiani ‘ncielu

e aspetti i peccaturi.

È chista l’orazioni

dicemula cu amuri

ludamu per eternu

lu Redenturi.

(Rosetta Di Maio)

Nenia religiosa

Oh Matri Santa di la pietati

‘mbrazza tiniti a Vostru Figliu mortu

datini ‘ntellettu e bona vuluntati

tinitini la storia a bon locu.

E ddu San Pietru chi l’avia niàtu

di la pena tuttu si pintiu,

arriva al postu e prestu fui spiatu

ca cci spiò all’afflittu cori di Maria:

“a lu tò mastru anni l’hai lassatu

‘mpopulamenti nun vinni cu tia?

a lu me mastru lu lassai attaccatu

‘menzu di tanti perfidi Giudei”.

E ora vieni Giuvanni me fidatu,

porta la nova di me Figliu dulci,

“Matri lu vitti a lu Monti Calvariu,

la cruci ‘ncuoddu e li chiova alli manu”.

Tutti li Santi a vidiri lu javunu

e javunu chianciennu a gàvuti vuci,

Ittati ‘na vuci Vui oh Matri mischina

ca Vostru Figliu ha fattu ‘na funtana.

Funtana funna di milli scaluna

a Vostru Figliu ci misiru la cruna.

Rit: E ccu lu dici tri voti lu jornu

un n’avi paura di peni d’Infernu.

E ccu lu dici tri voti la notti

un n’avi paura di la mala morti.

E ccu lu dici tri voti la simana

Iò peccu, Maria prega e Diu ‘ni pirduna.

Maria di n’attu a notti n’appi nova

mentri sò Figliu ran peni pateva

la porta a lu furgiaru aperta era

Idda cci dissi: “chi fai mastru astura?”

“fazzu ‘na lancia e tri spunta ddi chiova

ca servunu ppi lu figliu di Maria”.

Idda ittò un suspiru supra u scogliu

sula sulidda senza lu sò Figliu

“chiamatimi a Giuvanni ca lu vogliu,

quantu m’aiuta a chianciri a mmè Figliu”

Rit. (Antonina Lazzara)