Your basket is currently empty!

History of the monastery of San Giorgio: the only house of the Premonstratensians in Sicily

HISTORY

As one of the most recent scholars to deal with the abbey of San Giorgio in Gratteri has pointed out, it is undoubtedly a unique document of the culture and sensitivity of the Norman era at the height of its splendour (AGOSTARO F., San Giorgio in Gratteri. La storia intrigante di un monumento normanno, Ed. S. Marsala, Cefalù 2019, p. 9)

In reality, to understand the importance of these words, we need to go back to a very complex period of medieval history, the 12th century, and the decisive role played by Duke Roger of Altavilla (founder of the monastery of Gratteri) in consolidating the peace that had just been sealed between his father Roger, the first King of Sicily, and the legitimate Pope Innocent, who had recently forgiven him for siding with the anti-pope Anacleto (DI TELESE A., Ruggero II re di Sicilia, Cassino, Ciolfi, 2003, transl. it. by Vito Lo Curto; AUBÈ P., Ruggero II re di Sicilia, Calabria e Puglia: un normanno nel Mediterraneo, Milano 2006).

Indeed, on the death of Pope Honorius II (1130) a schism arose in the Church of Rome over the succession to the papal throne, which was resolved by a double election: one part of the cardinals elected Gregory Papareschi, who took the name of Innocent II, but the other part considered this election illegitimate and proceeded to another, electing Cardinal Pietro Pierleoni, who took the name of Anacleto II.

Both popes were consecrated and crowned on the same day, 23 February. However, almost all the Roman aristocracy, the majority of the lower clergy and the people of Rome recognised Anacleto II as the legitimate pope and in May Innocent II had to flee to France (BLOCH H., Montecassino in the middle ages, Rome 1986, p. 951-952).

However, decisive for the verdict on the legitimacy of the two pontificates was not the legal arguments, but the attitude of the Catholic world, which almost universally recognised Innocent II as pontiff. His most important supporters were Bernard of Chiaravalle, Abbot of Clairvaux, Norbert of Prémontré and King Lothar II of Germany.

Especially under Bernard’s influence, almost all European monarchs and bishops recognised the exiled Innocent II as Pope. The few secular lords who had initially supported Anacleto gradually abandoned his cause, believing it to be lost. Only the Norman Roger II remained on his side by having himself crowned King of Sicily by Anacleto II on Christmas night 1130 in the cathedral of Palermo (PIAZZONI A.M., Storia delle elezioni pontificie, p. 128).

It was in this year that the bishopric of Cefalù was founded and the first stone was laid for the construction of its cathedral, which was the same as the church of S. Giovanni degli Eremiti and the Cappella Palatina in Palermo. The constitution of the kingdom of Sicily was followed by a decade of wars, in which Roger II had the Pope Innocent II, Emperor Lothair II of Supplimburg, basileus John II Comnenus, the republics of Genova, Pisa and Venezia ganging up against him.

However, the Norman managed to defeat them all until a final decisive battle with the Pope’s troops in 1139 near San Germano. Chronicles of the time report that during the battle, Roger found refuge in the stronghold of Galluccio on the Garigliano, which was in turn besieged by the papal troops.

On that occasion, Innocent was taken prisoner by an ambush set by Roger’s eldest son, who took him to the castle of Mignano to meet his father. It is said that, on that occasion, the Norman threw himself at the feet of the Pontiff, asking him for forgiveness.

Three days later, on 25 July 1139, with the Treaty of Mignano, Innocent confirmed his father as King of Sicily, Roger as Duke of Puglia and his third son, Alfonso, as Prince of Capua (HOUBEN H., Ruggero II di Sicilia. Un sovrano tra oriente e occidente. Laterza ed., Roma-Bari 1999, pp. 100-126; DI CARPEGNA FALCONIERI T., Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 62, 2004).

A decisive role in the reconciliation between the King and the Pope was undoubtedly played by his eldest son Roger (founder of the monastery of Gratteri), a prince who knew how to manage power with wisdom and spirit, despite his young age. The historian of the time Romualdo Guarna, had no doubts about this, defining him as “vir quidem speciosus et miles strenuus, pius, benignus, misericors et a suo populo multum dilectus” (GUARNA R., Chronicon (a.M. 130 – a.C. 1178), edited by GARUFI C.. A., (Rerum italicarum scriptores, 127), Città di Castello, 1914, pp. 1-96).

It was against this backdrop of the peace that had just been achieved between the Norman and the Pontiff that the foundation of the priorate of San Giorgio in Gratteri took place, through the work of Roger, Duke of Puglia, eldest son of King Roger II, as can be deduced from a diploma of Tancred of 1191 confirming donations and privileges already granted and donating the hamlet of Amballut (ROLLUS RUBEUS, op. cit, pp. 64-65, manuscript f. 26 in Tabulario Belmonte also transcribed in GARUFI C.A., I documenti inediti dell’epoca normanna in Sicilia; parte I; tip. Lo Statuto, Palermo 1899, pp. 247-248).

With regard to the choice of site, this could be justified by the fact that the territory of Gratteri fell within the bishopric of Cefalù, the moral seat of the Kingdom, so much so that Roger himself had two sarcophagi placed inside the cathedral basilica that were to contain his remains after his death (VALENZIANO C., La basilica cattedrale di Cefalù nel periodo normanno; in “O teologo”, V/n. 19, Palermo 1987).

In any case, other interesting details also emerge from another significant document, the diploma of Lucius III of 1182, which makes it possible to establish the approximate date of foundation of the monastery, since it is reported that it was recognised and protected by two popes, Innocent II and Lucius II, so it is presumed, given that the first pope died in 1143, that its construction began around 1140 (ROLLUS RUBEUS, op. cit. original in Tabulario Belmonte, manuscript 37 in PIRRO R., Sicilia Sacra. Disquisitiones et notitiis illustrata, edited by MONGITORE A.. Tomo II, Palermo 1733, p. 839 3 ff., already in AGOSTARO F., p. 19).

Another relevant piece of information that can be deduced from the reading of the above-mentioned source concerns the significant settlement, already at that date, of the Premostratensian canons, a religious order just founded in the north of France that had in Gratteri their only abode in Sicily (BACKMUND N., Monasticon premostratensis, I, Strabing 1951, p. 874).

The diploma of Lucius III, in fact, constitutes the response to the pleas of Prior John and his confreres of the church of St. George with which the pope accepts their requests highlighting the link with the past and reassures them with the detailed confirmation of all the possessions and benefits granted by their predecessors (AGOSTARO F., op. cit. p. 19).

For this reason, some scholars who have dealt with the monastery of Gratteri – such as Backmund himself, a Premonstratensian canon – argue for a different original foundation, probably Cistercian, which would precede, for a short period, the presence of the Norbertine order (BACKMUND N., pp. 374-396).

These considerations arose from the identification of Cistercian stylistic elements observable in the structural characteristics of the building (See CAPITUMMINO F., L’abbazia normanna di S. Giorgio a Gratteri. La prima Fondazione cistercense in Sicilia? In “Convivium” IV/2, 2017 pp. 32-51).

In reality, both Norbert of Xanten (founder of the Premonstratensian order) and Bernard of Chiaravalle (famous Cistercian abbot) were two very important figures of the 12th century, so much so that the universal recognition of Innocent and the final victory over Anacleto should be ascribed mainly to the work of both of them (DI CARPEGNA FALCONIERI T., Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 62, 2004).

In any case, as the historian Salvatore Fodale has observed, Roger II’s main intention was to consolidate his power also through the replacement of the Greek Orthodox clergy linked to Byzantium with Latin clergy over whom he could exercise the right of “legatia” (FODALE S., Fondazione e rifondazioni episcopali in Sicilia da Ruggero II a Guglielmo III, in Potere e società in Sicilia – L’età normanna. Atti del convegno internazionale: Cefalù 7-8 aprile 1984 a cura di Gaetano Zito, Ed. SEI, Torino 1995, pp. 51-59).

During the Norman era and later in the Suevian era, the monastery and its church were endowed with various benefices, including farmhouses, mills, land and peasants for the sustenance of its monks. Therefore, if at the time of its foundation it was considered “pauper et esiguo”, it became “conspicuo et dives” in the 13th century (BACKMUND N., op. cit. p. 874, already in AGOSTATO F., p. 21).

In any case, the presence of an abbot in the 13th century certainly suggests that the priory had become an abbey perhaps because it had passed to the Augustinian order (AGOSTARO F., op. cit., p. 21). In fact, a letter of pope Alexander IV dated 15 March 1257 shows that the monastery had already passed to another order, the Augustinians, at that date and had probably been aggregated to the cathedral of Cefalù (DE LOYE J. – DE GENIVOL P., Les registres d’Alexandro IV, Tomo II, Paris 1917, Doc. 1913, p. 591).

From 1300 onwards, the church of St. George and its fiefdom passed to the “Hospitallers”, also known as the Knight of St. John, a military religious order, founded in the wake of the Crusades, “made up of a minority of frates milites who dedicated themselves to the defence of the holy places and other brethren who resided in preceptories, also known as commanderies” (SALERNO M. – TMASPOEG K., L’inchiesta pontificia del 1373 sugli Ospedali di S. Giovanni di Gerusalemme nel mezzogiorno d’Italia, Bari 2008 già in AGOSTARO F., p. 22).

The latter also had an economic function, that of producing income in the form of taxes to be sent to the Holy Land to support their activities. In fact, the Order’s main task was to assist “God’s travellers”, whether sick or in need. A hospital had been founded in Jerusalem for this purpose, dedicated to St. John the Baptist, and it was for this reason that the members of the Order also took the name “Jerusalemites and Hospitallers” (AGOSTARO F., op. cit., p. 22).

However, even though St George’s was a benefice of the Hospitallers of Jerusalem, who depended directly on the Apostolic See, its revenues were either managed by the local bishop who legitimately complied with papal provisions or entrusted to delegated administrators, as can be seen from an enquiry into the assets of the Hospitallers in southern Italy in 1373.

The document shows that, in that year, the church of San Giorgio had a layman named Pagano as its tutor, who was about 40 years old and had an annual income of 2 ounces of gold (SALERNO M. – TMASPOEG K., op. cit., pp. 271-274 already in AGOSTARO F., pp. 22-23).

After a series of vicissitudes involving Don Antonio Ventimiglia, Baron of Gratteri, who claimed for himself the right to exercise patronage in a period of feudal anarchy, the church was briefly assigned to the Augustinians and then in 1414 returned to the Hospitallers as a commandery together with that of Marsala (FODALE S., op. cit. already in AGOSTRARO F., p. 25).

In 1511 the Abbey of San Giorgio was subject to the right of royal patronage (BARBIERI G.. L., Beneficia ecclesiastica, edited by PERI I., V. I (Vescovati e abazie) ed. Manfredi, Palermo 1952, p. 218). The status of “preceptory” or “commandery” in which the monastic settlement found itself, entrusted for centuries to unscrupulous religious and lay people whose only interest was the exploitation of its assets, led to the progressive structural decay until the destruction and consequent spoliation of the building (AGOSTARO F., op. cit., p. 26).

Recently, new and significant documents relating to the Abbey of San Giorgio of Gratteri have been found in the archives of the Commandery of the Knights of Malta della Magione (AOM 6098, cc. 60 ff.). From what can be deduced from a first consultation of the documents, that of Gratteri belonged in modern times to the Commandery of San Giovanni Battista of Modica Randazzo, one of the most important and conspicuous in Sicily.

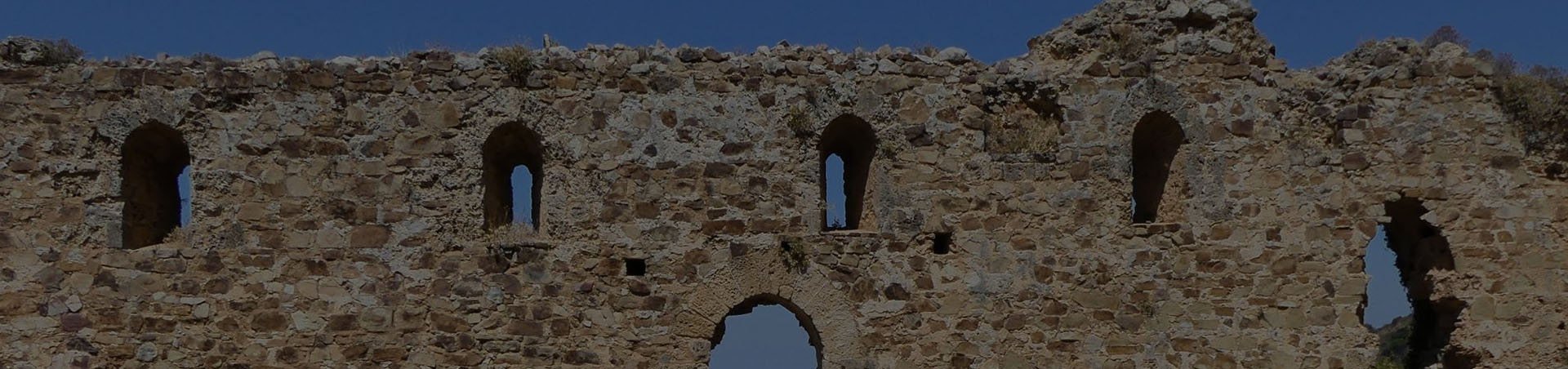

In Gratteri (AOM 6098, cc. 60 ff.), the Commandery owned the fief of San Giorgio, extending over 12 ares, located in the district of the same name, with a ruined church “in the middle of which there is a small church” dedicated to the Holy Knight. Already in 1628, this church was “ruined many years ago” and without a roof.

The main chapel faced east, towards noon there was another new ‘little chapel’ “voltata a dammuso“, with an altar with an image of the Madonna and a wooden carved crucifix, and to the side of the main chapel there was another ‘little chapel’. There were 12 windows in the church, six on each side. There was also a courtyard: a ‘baglio detto palo, seu carcera dell’animali‘ (Magione 404, c. 150).

In 1665, it is stated that the church was 12 rods long and 8 rods wide, and the fief extended to 108 “salme” (Magione 405). As early as 1720, the church no longer appears (Magione 407 (1720) c. 406 ff.). In the visit of 1749 it was ‘ruined’: it was decided to deconsecrate it and dedicate an altar to St George in the commendal church of Modica, or to place a painting of the saint in an altar already existing there (Visita 1749).

In 1780, in fact, the building was no longer mentioned definitively (Magione 409 1780 c. 468) (Cf: PACE G., La commenda di Modica-Randazzo, pp. 190-220 in BUONO L., PACE G., La Sicilia dei Cavalieri, Le istituzioni dell’Ordine di Malta in età moderna, Rome 2003).

In fact, a perusal of the “Riveli di beni e anime della terra di Gratteri” kept at the State Archive of Palermo shows that the fief of San Giorgio, from 1616 until 1811, was always held in Commendation of the Sacred Religion Jerusalemite of the Knights of Malta (ASP, Riveli, 1616-1811).

At the beginning of the 18th century, when Napoleon suppressed the Priory, the feud was sold to Don Pietro Cancila, cavalry lieutenant of Val Demone (SCELSI I., op. cit., p. 68). From consulting the archives, we know that the latter held the office of Mayor of Gratteri from 1856 to 1860 (ASP, LARGE ARCHIVE GANCIA – Acts of the “Civil Status” – Gratteri 1820-65).

The church, with various changes of ownership, remained in private hands until the 1980s when the Gratteri Town Council finally decided to acquire ownership (AGOSTARO F., op. cit., p. 26). To this day, the destruction of the monastery of San Giorgio is certainly one of those stories that is still little known, whose motivations are fuelled by fanciful legends of hidden treasures and folk tales of “evils by those corrupt monks massacred by the villagers for having abused some women” (LANZA A., La casa sulla montagna, Domodossola 1941).

It is probable, therefore, that the Canonìa was razed to the ground by the enraged villagers, but was subsequently also affected by a vast landslide that has rendered its typology and icnography illegible (TULLIO A., Gratteri, Chiesa di San Giorgio. L’indagine archeologica del 1991 in Arte e storia delle Madonie, Studi per Nico Marino, Voll. VII-VIII, Cefalù 2019, pp. 189-195).

ARCHITECTURE

Bearing in mind that the architecture of the churches was entrusted to the monastic orders that settled there, the Abbey of San Giorgio retains the characteristics of Sicilian Norman architecture, enriched with certain Nordic decorative typologies of French Romanesque with reminiscences of Arab culture.

We can even consider this church to be one of the most genuine expressions of European Romanesque culture, on a par with the cathedrals of Cefalù and Monreale. In fact, the main sources of inspiration for the construction of San Giorgio’s were the cathedral of Cefalù, the stylistic features of Romanesque art and the decorative features brought by the Augustinians from northern France.

The ruins of the church describe a building of classical Romanesque style, with three naves and a large central apse, in front of the entrance door, without a protruding transept at the sides, a form also favoured by Norman architecture. The basilica-like structure was divided by two systems of columns or pillars whose arches were inserted into the back wall directly next to the apse and marked the lines of convergence on the sanctuary (AGOSTARO F., op. cit., p. 30).

On the outside, the apse is in the form of a large drum divided by pilasters which accentuate the vertical thrust and immediately recall the apse of Cefalù cathedral, as does the portal, with a Romanesque arch slightly raised at the apex (reminiscent of the ogival arch in Islamic architecture), crowned by a decoration of staggered sticks forming the typical chessboard motif dear to Norman art (very common in Normandy), resting on two sculpted capitals, one with a palmette and the other with two rosettes resting on a star motif (TULLIO A.. , op. cit., pp. 189-195).

The characteristics of the ruin document a set of cultural and aesthetic contaminations, reworked in the historical context of Norman Sicily. Therefore, a probable collaboration of workers who were building the two churches almost at the same time cannot be excluded (AGOSTARO F., pp. 42-49).

As for the decorative elements, according to a study by the architect Giuseppe Samonà, these are certainly linked to the 12th century style of northern France, such as the decoration of the capitals, one with palmettes and the other with geometric stars, as well as the narrow slit and oculus windows on the façade (SAMONA’G., Monumenti medioevali nel retroterra di Cefalù, Stab. Ed. Meridioneli, Naples 1953, p. 8, already in AGOSTARO F., pp. 31-43).

In this regard, as pointed out by one of the greatest experts in sacred art, Don Crispino Valenziano, the structural and architectural characteristics of the monastic complex of Gratteri are to be linked to those of the coeval French monastery of the Holy Trinity in La Lucerne, in lower Normandy, hypothesising an architectural exchange between the church of Gratteri and that of La Lucerne, with which the Premonstratensians of San Giorgio would have had continuous relations (VALENZIANO C., La basilica cattedrale di Cefalù nel periodo normanno; in “O teologo”, V/n. 19, Palermo 1987, already in AGOSTARO F., p. 43).

Among the archaeological finds unearthed during some conservation work carried out in 1991 are three Nordic style capitals that take up the decorations and the half-relief sculptural style as found in northern France. One of them is decorated with palmette motifs similar to those on the portal capital, the second with figures of lambs on all four sides, the third with a crown of roses.

Another find was discovered in the 1980s outside the church in the eastern direction. It was the base of finely carved coupled columns. The artefact shows the sculptural characteristics of the decoration of the founding period. Sculpted in relief, a dragon (or salamander) wraps its tail around the columns and carries a disc between its legs, divided into eight parts by a cross and an X superimposed on it.

An allegory that remains to be deciphered, probably linked to the titular saint. During restoration work, on the south wall inside the church, traces of geometric studies inscribed in a circle were still visible, perhaps intended for decoration of the oculus windows (AGOSTARO F., op. cit. pp. 34-40).

In fact, the illustrative technical report written on that occasion by architects Culotta and Leone states: “there are more or less elaborate designs that can be framed in the cosmatesque repertoire and recur in many medieval churches in Italy, particularly in Sicily and in the contemporary Cathedral Basilica of Cefalù.

However, the existence of some precious engravings on the stucco that covered the walls testifies to the presence of skilled draughtsmen on site, traces of which have remained, leading to the idea of preliminary studies for the decoration of the floor and some of the plutei. These are parts of some ornamental geometric designs, grouped together in the southwest corner of the basilica hall, on the south wall.

They were probably part of an organic decorative project and are an important testimony to the use of drawing in medieval design” (Arch.tti CULOTTA e LEONE, Relazione tecnica illustrativa per l’acquisto e il restauro della Basilica di San Giorgio, Cefalù, 1988).

Along the north wall, a stepped access to the connecting door of the church was found, which joined the latter to the monastic structures where a large quadrangular area bordered by the remains of wall structures is located. To the west, on the other hand, the survey revealed the presence of a burial area where three monumental sarcophagus tombs were identified (TULLIO A., op. cit., pp. 194-195).

Finally, the recent and last excavation campaign in 2020 brought to light the remains of tombs and other significant finds from the Canonìa, such as, for example, capitals decorated with fantastic figures of dragons or with zoomorphic figures such as vultures and birds of prey, which, in the Middle Ages, were associated with the divinatory symbols of ancient alchemists.

In fact, it is precisely these latter findings that bear witness to important influences of the Nordic sculptural style, which would seem to be related to those already present in the nearby cathedral of Cefalù. Today the abbey is part of the heritage of the municipality of Gratteri, with the ambitious aim of bringing the property within the Arab-Norman UNESCO site.

WHO WERE THE PREMONSTRATENSIAN CANONS REGULAR?

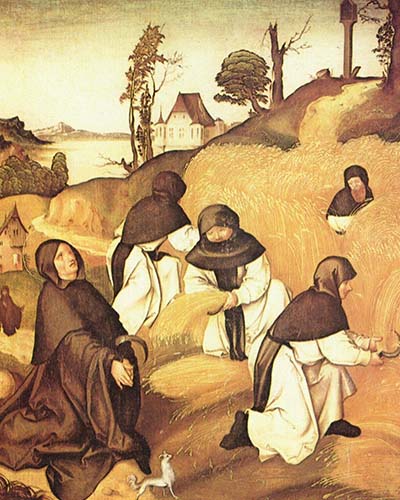

“They are seen arriving in two, because the apostles, in the gospels, go two by two. The preacher is dressed like a hermit, with clothes of wool, lamb or goat skins. A cloak and a hood complete his attire” (PETIT F., Norbert et l’origine des Prémontrés, Les édiction du Cerf, Paris 1981, pp. 111-113, already in AGOSTARO F., p. 56).

The order of canons regular of Prémontrés, also called Premonstratensians, Norbertines or Canons blanche, were founded by Saint Norbert of Xanten at the beginning of the twelfth century at the dawn of the great reform movement for the return to an authentic evangelical spirit with reference to the Augustinian rule after the internal lacerations of the Church.

Norbert, who came from a noble Rhenish family, entered the ecclesiastical state at a very young age and was appointed canon of the collegiate church of Xanten. He was educated in the archbishop’s palace in Cologne and lived for some years at the court of Emperor Henry V of Franconia (VELVEKENS J.B., Bibliotheca Sanctorum, 1050-1068). While walking between Xanten and Vreden he was almost struck by lightning and decided to abandon all worldliness and enter the monastery of St Benedict in Siegburg. In 1115 he was ordained a priest and decided to devote himself entirely to itinerant preaching, and a large number of followers gathered around him.

Pope Gelasius II, whom Norbert wanted to meet at Saint-Gilles, approved of his way of life and Pope Calixtus II recommended him to the Bishop of Laon, who invited him to found a monastery in his diocese. On 25 December 1121 Norbert and his followers settled in Prémontré (Premonstratum in Latin, hence the name of the order), near Laon, where they took their vows and began to lead a common life according to the rule of St Augustine in the abbey of Prémontré, which became the mother abbey of the new order.

The Premonstratensian order was approved by Pope Honorius II with the bull Apostolicae disciplinae of 19 May 1126. (VELVEKENS J.B., Dictionary of the Institutes of Perfection, coll. 720-731).

The order spread rapidly in France, in the territories of the Empire, in Eastern Europe (especially Hungary) and in Palestine, where the canons arrived at the time of the Crusades. The first years of their history coincided with their period of greatest splendour, characterised by a strict observance of the rule and an intense intellectual life, but between the 13th and 14th centuries the decline of the Premonstratensians began (IBIDEM).

As Agostaro noted, the fundamental peculiarity of the order was to combine monastic life, consisting of prayer and work, with the apostolate outside the monastery. The Premonstratensians were, in the understanding of its founder, a religious order made up of canons regular, but also of apostles, itinerant preachers who, having fulfilled their ministry, returned to live together in prayer, poverty and work (AGOSTARO F., op. cit. p. 54).

The Premonstratensian Canons Regular, in fact, are priests who combine the contemplative life with the exercise of sacred ministry such as liturgical worship, parish ministry, but also education of youth and missionary apostolate.

Here is how F. Petit describes them: “In order for Christian life to be open to both men and women, Nobert wanted there to be two houses around the church: one for men, clerics and converts, and one for men and women” (PETIT F., La spiritualité des Prémontrés aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles, Paris 1947, in translation, p. 19, already in AGOSTARO F., p. 54).

In Gratteri, for example, according to some folk tales, it is said that the children of the noble and wealthier classes went to study in the past with the religious of San Giorgio, who taught them the knowledge of the arts, herbs and the stars (FRAGALE M., ethnotexts 2020).

But in any case, the stay of the Premonstratensian canons at San Giorgio lasted for the limited time of about 100 years, those between the foundation of the monastery and their disappearance from Gratteri before 1257 (AGOSTARO F., op. cit., p. 50).

Marco Fragale

(Università di Palermo)

Bibliografia:

AGOSTARO F., San Giorgio in Gratteri. La storia intrigante di un monumento normanno, Ed. S. Marsala, Cefalù 2019

ASP, GRANDE ARCHIVIO GANCIA – Atti dello “Stato Civile” – Gratteri 1820-65).

ASP, Riveli, (1616-1811) ricerche a cura di M. FRAGALE

AUBÈ P., Ruggero II re di Sicilia, Calabria e Puglia: un normanno nel Mediterraneo, Milano 2006

BACKMUND N., Monasticon premostratensis, I, Strabing 1951

BARBIERI G. L., Beneficia ecclesiastica, a c. d. PERI I., V. I (Vescovati e abazie) ed. Manfredi, Palermo 1952

BLOCH H., Montecassino in the middle ages, Roma 1986, p. 951–952

CAPITUMMINO F., L’abbazia normanna di S. Giorgio a Gratteri. La prima fondazione cistercense in Sicilia? In “Convivium” IV/2, 2017 pp. 32-51

CULOTTA P. e LEONE G., Relazione tecnica illustrativa per l’acquisto e il restauro della Basilica di San Giorgio, Cefalù, 1988

DE LOYE J. – DE GENIVOL P., Les registres d’Alexandro IV, Tomo II, Paris 1917, Doc. 1913

DI CARPEGNA FALCONIERI T., Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, vol. 62 (2004)

DI TELESE A., Ruggero II re di Sicilia, trad. it. di Vito Lo Curto Cassino, Ciolfi, 2003

FODALE S., Fondazione e rifondazioni episcopali in Sicilia da Ruggero II a Guglielmo III, in Potere e società in Sicilia – L’età normanna. Atti del convegno internazionale: Cefalù 7-8 aprile 1984 a cura di Gaetano Zito, Ed. SEI, Torino 1995, pp. 51-59

GUARNA R., Chronicon (a.M. 130 – a.C. 1178), a cura di GARUFI C. A., (Rerum italicarum scriptores, 127), Città di Castello, 1914

HOUBEN H., Ruggero II di Sicilia. Un sovrano tra oriente e occidente. Laterza ed., Roma-Bari 1999

LANZA A., La casa sulla montagna, Domodossola 1941

PACE G., La commenda di Modica-Randazzo, pp. 190-220 in BUONO L., PACE G., La Sicilia dei Cavalieri, Le istituzioni dell’Ordine di Malta in età moderna, Roma 2003

PETIT F., La spiritualité des Prémontrés aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles, Paris 1947

PETIT F., Norbert et l’origine des Prémontrés, Les édiction du Cerf, Paris 1981

PIAZZONI A.M., Storia delle elezioni pontificie, 2003

PIRRO R., Sicilia Sacra. Disquisitiones et notitiis illustrata, a cura di MONGITORE A. Tomo II, Palermo 1733

ROLLUS RUBEUS in Tabulario Belmonte trascritto anche in GARUFI C.A., I documenti inediti dell’epoca normanna in Sicilia; parte I; tip. Lo Statuto, Palermo 1899

SALERNO M. – TMASPOEG K., L’inchiesta pontificia del 1373 sugli Ospedali di S. Giovanni di Gerusalemme nel mezzogiorno d’Italia, Bari 2008

SAMONA’G., Monumenti medioevali nel retroterra di Cefalù, Stab. Ed. Meridioneli, Napoli 1953

SCELSI I., Gratteri. Storia, cultura, tradizioni. Tip. Valenziano, Cefalù 2008

TERREGINO G., Il regale cenobio dei Premostratensi a Gratteri, in gratteri.org, luglio 2018

TERREGINO G., L’abbazia di San Giorgio, documento storico singolare e incancellabile, in gratteri.org, aprile 2020

TERREGINO G., L’Abbazia di San Giorgio frutto della pace tra Papa e Re, in gratteri.org, agosto 2020

TULLIO A., Gratteri, Chiesa di San Giorgio. L’indagine archeologica del 1991 in Arte e storia delle Madonie, Studi per Nico Marino, Voll. VII-VIII, Cefalù 2019

VALENZIANO C., La basilica cattedrale di Cefalù nel periodo normanno; in “O teologo”, V/n. 19, Palermo 1987

VELVEKENS J.B., Bibliotheca Sanctorum, coll. 1050-1068

VELVEKENS J.B., Dizionario degli Istituti di Perfezione, coll. 720-731